Data icebergs and the urgency for environmental action: Making data infrastructures interoperable and effective during the UN Ocean Conference 2022 in Lisbon

By: Paul Dunshirn

What kind of data do we need to put a halt to the on-going deterioration of ocean ecosystems and to deter connected threats to human societies? How can we make this data accessible and usable to a wider range of stakeholders? What are the challenges in making data ‘speak truth’ to policy makers?

These and related questions about the availability and uptake of data and science were high on the agenda during the overall second UN Ocean Conference (UNOC 2022), which took place in Lisbon during the final week of June. About 6000 persons including 24 heads of state and over 2000 stakeholders from civil society came together to engage in conversations about the role of science and innovation in achieving sustainable development goal number 14 - “Life below Water”. Next to opportunities for networking, UNOC 2022 provided a space for state representatives and UN institutions to announce voluntary commitments and promote alliances for higher standards in environmental protection. For instance, several Latin American countries committed to implementing a significant number of new marine protected areas. The Alliance of Small Island States (AOSIS) announced their declaration on the enhancement of marine scientific knowledge, research capacity and transfer of marine technology. The conference featured various official plenary meetings, but also a large number of side events focused on concrete issues of ocean governance.

Around 6000 persons attended the UN Ocean Conference 2022 in Lisbon. Source: own image.

Paul Dunshirn from the Research Platform Governance of Digital Practices and the ERC-funded project MARIPOLDATA attended UNOC 2022 as a researcher in the field of marine genetic resources and genetic sequence data. He paid close attention to the proceedings related to data governance, to global imbalances in capacities to contribute and to use existing data infrastructures, as well as to the challenges in translating available information into actual social or political responses. This blog summarises Paul’s experiences and sketches out the pressing issues in this field, which include: the necessary expansion of data collection on deep sea ecosystems; making existing databases more easily available and interoperable; and considering social dimensions (i.e. ‘humans’) in the design of these infrastructures.

The need for ‘more data’ to counteract environmental threats and effectively protect marine biodiversity

Most of the data-related events at UNOC 2022 were connected to the UN Ocean Decade (2021-2030) - a framework for events, stakeholder mobilisation, and investment into various types of ocean-related sciences to better understand and bring about the conditions for sustainable ocean ecosystems. The decade focuses on various thematic areas, which includes protecting and restoring marine biodiversity, advancing blue economies for the sustainable and equitable use of ocean resources, preparing societies to cope with ocean hazards, and better understanding the crucial role the ocean plays in absorbing climate change. It also entails a focus on the collection of data and the construction of open and interoperable databases to support stakeholders and decision-makers in achieving these goals.

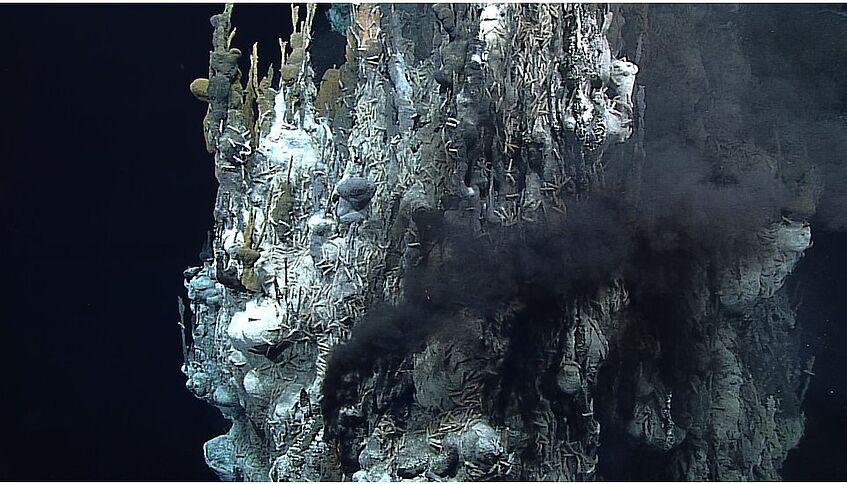

A good example for a policy issue that cannot be properly addressed at present due to a lack of data and knowledge is deep seabed mining. This topic was the most controversial topic during UNOC 2022. The UN institution responsible for the international seabed Area, the International Seabed Authority (ISA), is currently working on a mining code under which the exploitation of mineral resources should be allowed. While some governments and companies push for such a code, scientists and an increasing number of states are calling for a ban on deep seabed mining until more is known about its impact on deep sea biodiversity and ecosystems (including the important services they provide). One of the assumptions around the exploration of deep sea minerals has been that mining in these areas will be of comparatively little environmental harm, due to an assumed lack of life at these depths. However, recent technological advancements have enabled marine biologists to explore what appears to be surprisingly rich deep sea biodiversity. Besides the ecosystem services these species provide, they constitute a yet widely unexplored pool of genetic resources of presumably high commercial value due to the hostile conditions they manage to survive in. In this light, it is important to expand and systematise data collection on deep sea biodiversity to get a clearer picture of potential impacts.

Deep sea hydrothermal vent systems are biodiversity hotspots as well as promising areas for mining activities. Source: NOAA Ocean Exploration.

The need for more data, monitoring, and science also featured in connection with a range of other topics at UNOC 2022. High on the agenda was the importance of ocean ecosystems as providers of climate services, such as in fixing and processing CO2. These services have been prominently acknowledged in the recent Glasgow Climate Pact. In this regard, the Tara Oceans Foundation organised an interesting event highlighting the curious lack of research and discussion about the ocean microbiome (such as plankton) for dealing with climate change. While climate services provided by mangroves or seaweed may get consideration in the identification of marine protected areas, more data is needed to understand and to start protecting the ocean’s microscopic biodiversity as well.

Challenges in data interoperability and private-public partnerships

Deep sea and microscopic biodiversity monitoring are just two of many data-related areas that were discussed during UNOC 2022. Indeed, many representatives from companies, organisations, and institutions in charge of building and managing ocean data infrastructures were present at UNOC 2022. Besides discussing the need for more data for particular purposes, a lot of focus was put on how to use already available data to increase effectiveness.

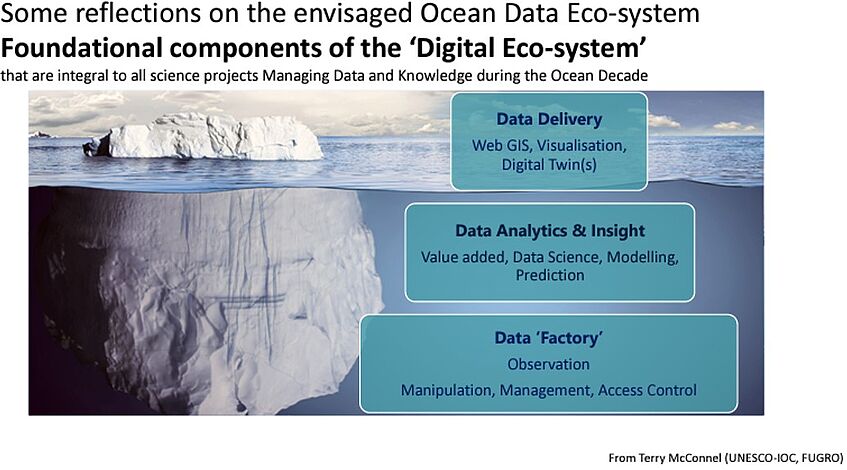

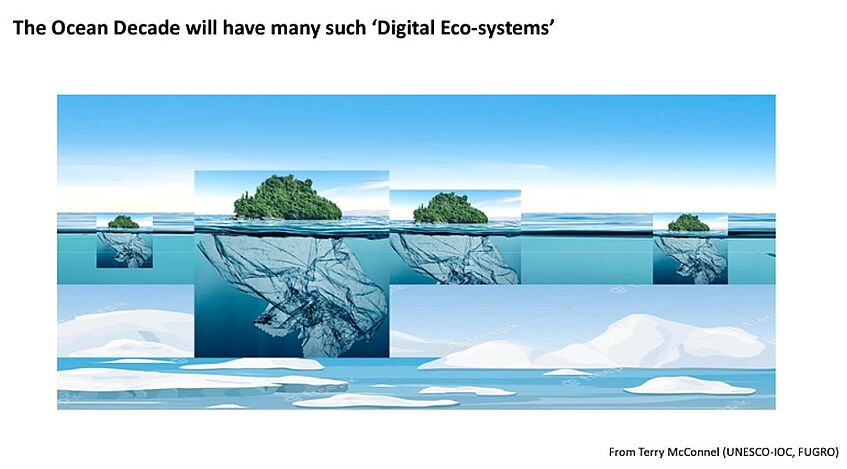

For example, representatives from the European Marine Observation and Data Network (EMODNET), the UN Ocean Decade Data Coordination Group, the Global Ocean Observing System (GOOS), Mercator Ocean International, private geo-spatial company Fugro, and several regional organisations came together for a side event to discuss interoperability of existing ocean databases. At this event, every speaker presented a ‘data iceberg’, which was an allegory used to refer to the distinct databases that each one of these organisations manage. The invisible elements of a data iceberg are the major components of data creation (or data factory) and data analytics happening inside an organisational unit. Only the tip of the iceberg, the visualisation and communication of information to relevant stakeholders is what is typically visible to the public (yet crucial in stirring necessary environmental actions).

In the case of these data infrastructures, the main challenges are not in creating more data, but to improve interoperability through standardisation and inter-organizational cooperation. As one moderator put it, ‘we already have very impressive icebergs’, but current efforts need to go into connecting these icebergs so as to allow analysing efficiently and effectively across databases.

For example, Ben Williams from Fugro talked about the complexity of sharing data held by a private company and created with client and shareholder interests in mind. He explained that not sharing data is oftentimes an intentional strategy in industry, as companies expect a return on their investment into new data infrastructures. However, Fugro does make certain subsets of their data public through targeted partnerships where possible. For instance, Fugro has a collaboration with EMODNET to share bathymetric data. Such data plays a crucial role in measuring water tides, temperature, or salinity in local and regional coastal areas and thus allows for predicting environmental hazards, such as tsunamis. Specific forms of cooperation and awareness in situations where private investment can equally benefit the public can bring about certain ‘cultural changes’ in data production and sharing, as Ben Williams argued during UNOC 2022.

Besides difficulties in making private-public partnerships work, the case of Tsunami prediction is also a useful example for understanding challenges in making databases interoperable, such as integrating similar but disparate regional infrastructures. Tsunami Service Providers (TSP) already exist for specific ocean regions, but IOC-UNESCO is working on standardising data collected through different providers and thus to increase the quality of predictions through its Global Tsunami Early Warning and Mitigation Programme. Another challenge in Tsunami prediction relates to the integration of different types of data. For instance, the already mentioned bathymetric data from local or regional monitoring systems are often limited in range and thus do not cover wide areas further out. In this case, bathymetric data could fruitfully be combined with satellite data to help predict hazards better, which would again require partnerships with providers thereof.

Co-designing data infrastructures with and for stakeholders

At a different side event entitled ‘Ocean and Coastal Observation and Monitoring at Scale’, the representative of GOOS emphasised the need to create incentives for regional data holders in order for them to engage in the work necessary for accomplishing cross-data base integration. This point links to the other focus of data-related events during UNOC 2022, which was the co-design of data infrastructures - the ‘human’ or ‘social’ dimension, as some of the speakers called it.

In this regard, a representative from the UN Division for Ocean Affairs and the Law of the Sea (UNDOALOS) reported from training courses they organise for policy makers to understand which data already exists and how to use it. Similarly, the representative of Mercator Ocean International explained that mobilisation of affected communities and additional financial resources were necessary in order to accomplish the above-mentioned integration of satellite data in coastal monitoring systems for environmental hazards. To foster this mobilisation, coastal observation systems need to become fully open and local capacities to actually use them need to improve. In this way, data infrastructures can transform into high value tools, allowing societies to scrutinise political decision-making in the face of environmental threats.

As was emphasised across the board, a lot more work needs to go into the communication and co-design of data infrastructure and knowledge for stakeholders to provide resources and to actually respond to these inputs. The representative of UNEP World Conservation Monitoring Centre emphasised the need to use data on biodiversity loss to explain dooming threats on marine ecotourism - oftentimes a crucial source of income for coastal communities. This communicative approach can work in that it explains not only the impact of environmental degradation on marine ecosystems, but also the following economic and social implications. In other words, choosing the languages that decision makers listen to and engaging affected publics is crucial to create the necessary political, economic, and social changes.

Panellists of the event on co-designing data infrastructures at UNOC 2022. Source: Own image.

Local efforts need to be supported by effective environmental treaties and strong international institutions

A lot needs to be done in order to accomplish the sustainable development goals and to build capacities and data infrastructures to support this process. As became clear during UNOC 2022, local activities by state or regional authorities, as well as by the scientific community itself play a crucial role.

To bring ocean monitoring to the required level of quality, efficiency, and equitability, local activities also need support at an international level. This not only relates to the discussed coordination efforts in scaling up and making databases interoperable. Even more crucial is the formation and implementation of international law, for which 2022 is a crucial year. As mentioned, the ISA will have an important role to play in considering the legitimacy of deep seabed mining in the face of a severely underdeveloped scientific knowledge about its impact. Similarly important, the fifth round of the negotiations on biodiversity beyond national jurisdiction (BBNJ negotiations) takes place in August. The BBNJ treaty will introduce a legal framework to regulate many of the topics discussed in this blog, including the creation of marine protected areas in international waters, as well environmental impact assessments (see this recent blog post by MARIPOLDATA and French think-tank IDDRI on implications of the UNOC 2022 for the BBNJ treaty).

An important element of the BBNJ treaty will be the creation of a central information hub to monitor activities in international waters (the so-called clearing house mechanism). Importantly, the experiences with ‘data icebergs’ discussed during UNOC 2022 bear crucial lessons when it comes to making already available databases accessible and interoperable. The extensive work behind these existing data infrastructures is also instructive on how to make necessary adjustments so that biodiversity targets can be met, and on how to find the right communicative angles so as to get relevant stakeholders on board for participating in the quest for effective environmental action. We hope that policy makers will be ambitious in considering data-related activities and needs in this regard.